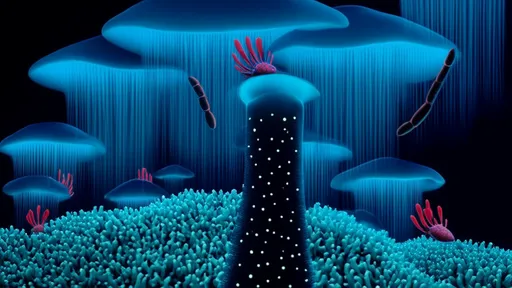

In the perpetual darkness of the deep sea, where pressure crushes and light never reaches, an extraordinary phenomenon unfolds—one that challenges our understanding of viral diversity and genetic innovation. Whale falls, the carcasses of deceased cetaceans that sink to the ocean floor, have long been recognized as oases of life in the abyss. But recent discoveries reveal these decaying giants serve as something far more unexpected: bustling hubs of viral evolution and CRISPR system development.

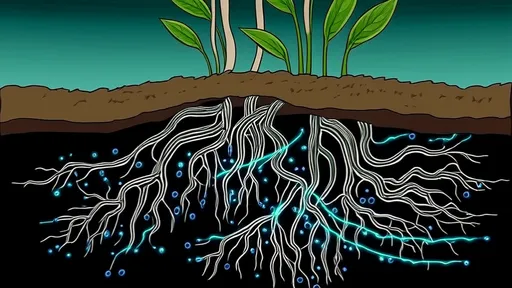

The term "whale fall" hardly does justice to the ecological theater that follows a 40-ton corpse's descent. As scavengers strip flesh and bone, a slower, more intricate drama plays out at the microbial level. Researchers sampling whale falls off California and Japan have uncovered viral populations ten times more diverse than in surrounding sediments. This viral menagerie doesn't represent destruction, but rather a genetic crucible—one that appears to be forging novel CRISPR systems in real time.

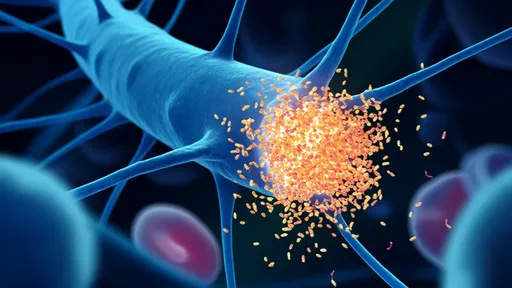

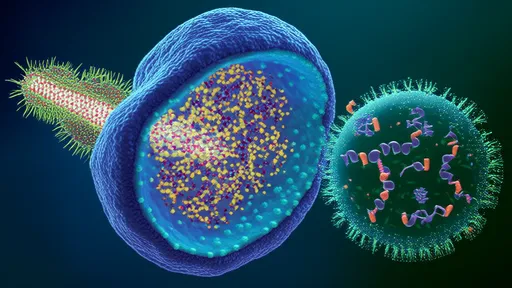

CRISPR, the revolutionary gene-editing tool that earned its discoverers a Nobel Prize, originates from bacterial immune systems. These molecular defenses allow microbes to "remember" viral invaders by storing snippets of viral DNA in their genomes. When the same virus attacks again, the bacterium uses CRISPR-associated (Cas) proteins to identify and cleave the invader's genetic material. What stunned scientists was finding CRISPR arrays not just in bacteria, but in the viruses themselves—a discovery made possible by sampling whale fall ecosystems.

The whale fall environment creates perfect conditions for this genetic arms race. As Dr. Helena Vasseur of the Monterey Bay Research Institute explains: "Imagine a sunken whale as Grand Central Station during rush hour, except every passenger is a microbe carrying genetic blueprints, and every train is a virus shuttling DNA between species. The exchange rate is staggering." Her team's metagenomic sequencing revealed viral genomes containing partial CRISPR systems, some with Cas proteins never before documented. These viral-encoded systems appear capable of targeting bacterial defenses—essentially hacking the hackers.

One particularly striking discovery came from a whale skeleton at 2,900 meters depth. Viruses there carried a streamlined CRISPR variant researchers dubbed "CRISPR-Lite"—a system lacking several core Cas proteins yet still functional. This pared-down editor suggests viruses may be evolving CRISPR systems toward efficiency rather than complexity. Parallel findings show bacterial CRISPR arrays containing viral sequences from multiple historical infections, creating a genomic "museum" of past pandemics at the microscopic scale.

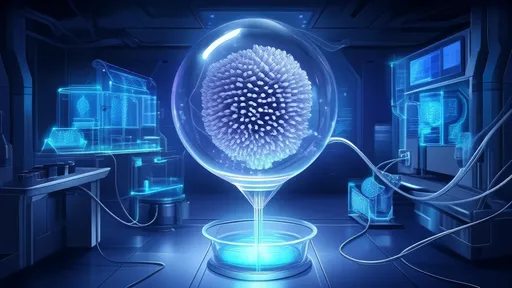

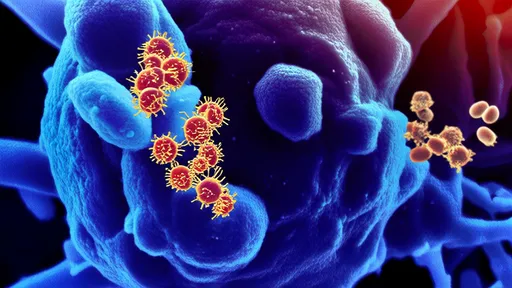

The implications extend beyond marine biology. Pharmaceutical researchers are particularly interested in whale fall viruses as potential sources of compact CRISPR systems. "Nature has spent millions of years miniaturizing these tools in extreme environments," notes synthetic biologist Dr. Raj Patel. "What we're seeing could lead to next-generation editors small enough to package into therapeutic viruses for gene therapy." Already, three newly discovered Cas proteins from whale fall viruses show promise in targeting antibiotic-resistant bacteria during lab tests.

Yet these discoveries raise ecological questions. Climate change and industrial whaling have reduced whale populations dramatically, potentially starving the deep sea of these viral diversity hotspots. Paleogenetic studies suggest historic whale fall densities were five times greater than current levels. As marine virologist Dr. Lin Yao warns: "We're not just losing whales—we're losing the evolutionary incubators their bodies create. Each whale that doesn't reach the seafloor represents thousands of unrealized genetic innovations." Conservation efforts now emphasize protecting whale populations not just for the animals themselves, but for the invisible, invaluable ecosystems their deaths sustain.

Ongoing research aims to catalog the full scope of whale fall viral diversity using autonomous deep-sea samplers. Early results suggest certain viral groups specialize in different decomposition stages, with some appearing only when sulfur-loving bacteria dominate years after the whale's arrival. This temporal specialization hints at viral "shift workers" taking turns to exploit changing resources—a phenomenon never before documented in viral ecology.

The whale fall discoveries underscore how much remains unknown about Earth's largest habitat. As sequencing technologies improve, researchers anticipate finding more exotic CRISPR variants and perhaps entirely new classes of genetic editors. What began as a curiosity about deep-sea decay has blossomed into a paradigm shift: that the remains of Earth's mightiest creatures foster some of its most sophisticated molecular machinery. In the crushing depths, where life persists against all odds, death gives birth to genetic revolution.

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025