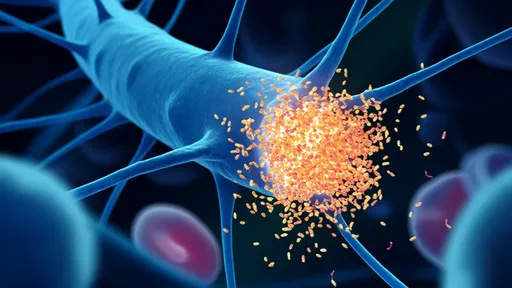

In the intricate landscape of Alzheimer’s disease research, a startling discovery has emerged: glial cells, long considered mere "support cells," may be acting as energy hijackers, stealing mitochondria from neurons and exacerbating neurodegeneration. This phenomenon, dubbed "mitochondrial stealing," challenges traditional views of cellular behavior in the brain and opens new avenues for understanding the metabolic dysfunction underlying Alzheimer’s.

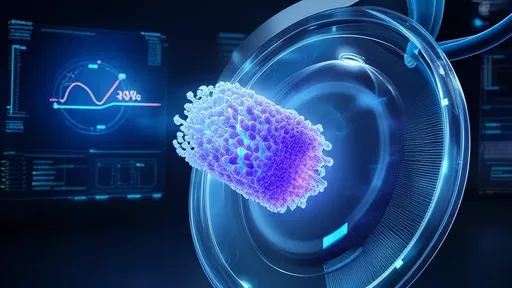

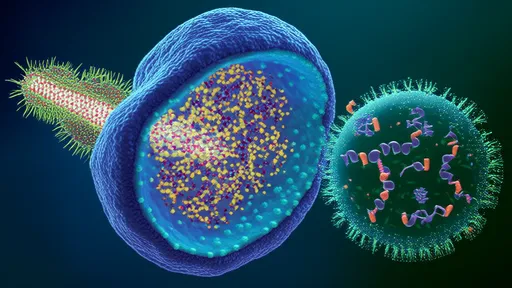

The brain’s energy economy is a delicate balance, with neurons demanding vast amounts of ATP to maintain synaptic activity and cellular integrity. Mitochondria, the powerhouses of the cell, are critical to meeting this demand. However, in Alzheimer’s patients, neurons increasingly struggle with energy deficits, leading to synaptic failure and cell death. For years, researchers attributed this to intrinsic mitochondrial dysfunction within neurons. But recent evidence suggests a more sinister plot—glial cells, particularly astrocytes and microglia, may be actively depriving neurons of their mitochondria.

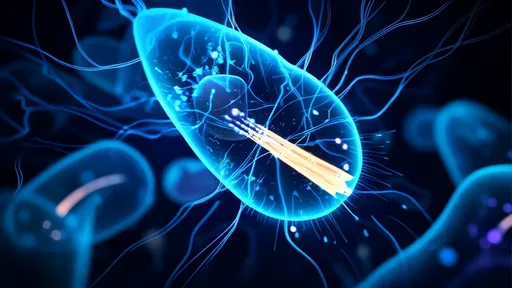

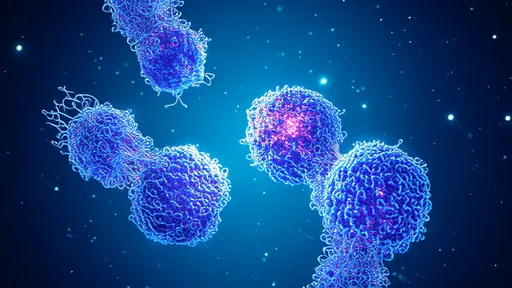

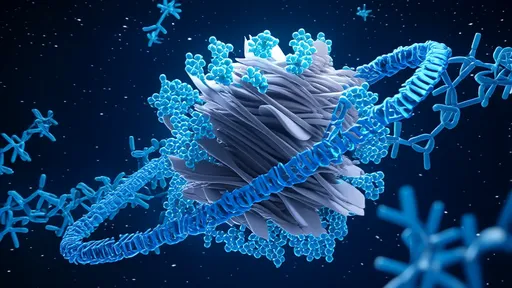

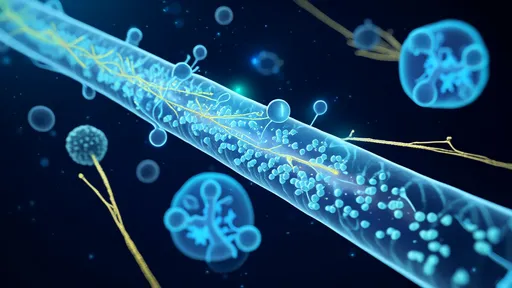

Astrocytes, the star-shaped glial cells, are essential for maintaining neuronal homeostasis. They provide nutrients, regulate neurotransmitters, and even recycle synaptic components. Yet, under the stress of Alzheimer’s pathology, these benevolent caretakers appear to turn predatory. Studies using advanced imaging techniques have captured astrocytes extending processes to physically siphon mitochondria from neuronal axons. This theft is facilitated by specialized structures resembling tunneling nanotubes, which act as intercellular highways for organelle transfer.

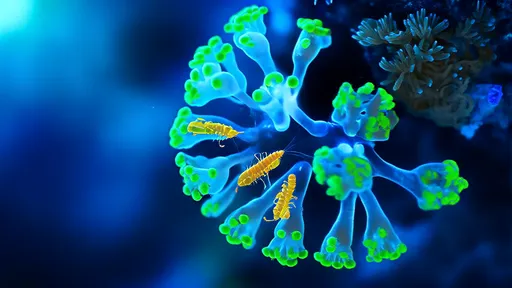

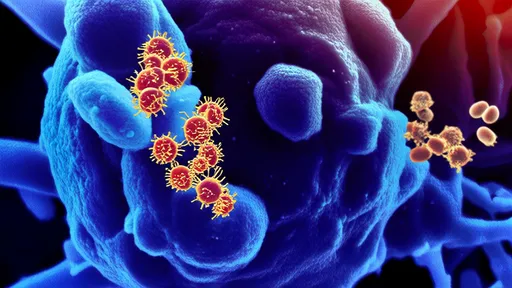

Microglia, the brain’s immune sentinels, are also implicated in this mitochondrial heist. In their role as scavengers, microglia typically engulf and degrade damaged neurons. However, in Alzheimer’s, they seem to prematurely strip functioning mitochondria from stressed but viable neurons, accelerating their decline. This behavior may be driven by the chronic inflammatory environment of the diseased brain, where microglia become hyperactive and lose their ability to distinguish between healthy and compromised cells.

The consequences of this glial-mediated mitochondrial theft are profound. Neurons, already struggling with amyloid-beta plaques and tau tangles, face an additional energy crisis. Deprived of sufficient mitochondria, they become increasingly vulnerable to excitotoxicity and oxidative stress. This creates a vicious cycle: as neurons weaken, glial cells may further exploit them, hastening neurodegeneration. The phenomenon also helps explain why therapies targeting neuronal mitochondria alone have shown limited success—the problem isn’t just internal dysfunction but external piracy.

What triggers glial cells to become energy thieves? One theory points to metabolic desperation. In Alzheimer’s, glial cells themselves suffer from energy shortages due to reduced glycolysis and impaired lactate shuttling. Stealing mitochondria from neurons may be a survival tactic, allowing glia to meet their own energy demands at the expense of their neighbors. Alternatively, the theft could be a maladaptive response to neuronal distress signals, where glia misinterpret stress cues as a call to remove "failing" organelles.

Therapeutic strategies are now being explored to intervene in this mitochondrial tug-of-war. Blocking the formation of tunneling nanotubes or inhibiting specific phagocytic pathways in glia could prevent mitochondrial theft. Another approach involves boosting neuronal defenses, perhaps by enhancing mitochondrial biogenesis or improving quality control mechanisms. Interestingly, some experimental drugs that modulate glial activity have shown promise in restoring neuronal mitochondrial populations, hinting at a potential path forward.

This discovery also reshapes our understanding of cellular collaboration in the brain. The traditional view of glia as passive supporters is giving way to a more nuanced perspective—one where these cells actively negotiate energy resources, sometimes cooperatively, sometimes competitively. In healthy brains, this dynamic balance ensures optimal function. But in Alzheimer’s, the rules of engagement break down, and glia become adversaries rather than allies.

As research progresses, key questions remain. Do all glial subtypes engage in mitochondrial theft, or are certain populations more culpable? Is this phenomenon unique to Alzheimer’s, or does it occur in other neurodegenerative diseases? And crucially, can we develop therapies that restore the symbiotic relationship between neurons and glia without compromising essential glial functions?

The revelation of glial cells as "energy hijackers" adds a compelling layer to the Alzheimer’s puzzle. It underscores the complexity of brain metabolism and the delicate interplay between cell types. While much work lies ahead, this paradigm shift offers fresh hope—that by understanding and addressing mitochondrial piracy, we might finally disrupt the relentless progression of this devastating disease.

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025