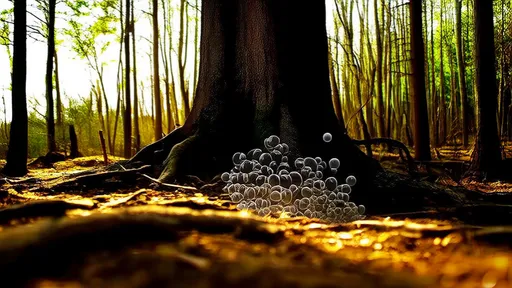

In the dense heart of old-growth forests, where sunlight filters through emerald canopies and roots intertwine with ancient soil, scientists have uncovered an unsettling phenomenon. Trees, long celebrated as Earth's carbon sinks, are revealing a hidden duality during periods of drought—they exhale methane, a greenhouse gas thirty times more potent than carbon dioxide. This discovery positions forests as unwitting "methane sentinels," their emissions serving as both a climate alarm and a biological mystery demanding urgent scrutiny.

The revelation challenges decades of ecological dogma. Until recently, methane production was considered the exclusive domain of waterlogged anaerobic environments—swamps, rice paddies, and the digestive tracts of livestock. But when researchers deployed laser-based spectrometers in drought-stricken woodlands from the Amazon to boreal regions, their instruments detected plumes of methane emanating from seemingly dry tree trunks. The quantities, while modest per individual tree, become staggering when scaled across millions of hectares of global forest.

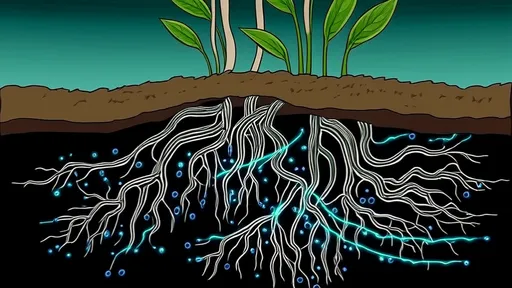

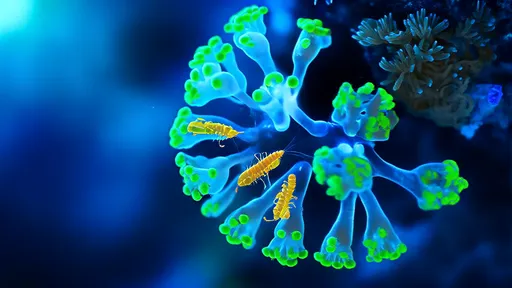

Drought acts as a gruesome puppeteer in this process. As soil moisture vanishes, tree roots secrete organic compounds to attract symbiotic fungi. These compounds inadvertently feed methane-producing archaea—microbes typically dormant in oxygen-rich soils. Simultaneously, water stress causes microscopic cracks in the heartwood, creating low-oxygen chambers where these microbes thrive. The tree, in its struggle to survive, becomes a chimney for greenhouse gases.

What makes this phenomenon particularly insidious is its timing. Droughts are intensifying worldwide due to climate change, creating a vicious cycle: rising temperatures trigger forest methane emissions, which accelerate warming, prompting more droughts. Satellite data analyzed by the European Space Agency shows methane hotspots coinciding with regions experiencing "hydraulic failure" in trees—a condition where water columns within trunks snap under tension like overstretched rubber bands.

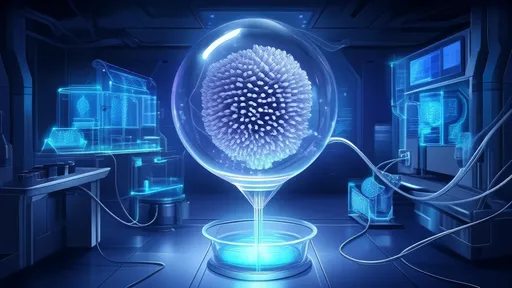

The silver lining, if one exists, lies in early detection. Because trees begin emitting methane weeks before showing visible signs of drought stress, forest emissions could serve as an early warning system. The University of Cambridge's Biosphere-Climate Interaction Group has prototype "tree breath analyzers"—miniaturized sensors that attach to tree trunks and transmit real-time methane data via satellite networks. During trials in Germany's Black Forest, these devices detected methane surges three weeks before traditional soil moisture alarms were triggered.

Indigenous knowledge systems appear to have anticipated this science. The Yawanawá people of the Brazilian Amazon have long spoken of "the forest's fever breath" during dry spells—an observation modern instrumentation now validates. Their elders describe vines emitting warm gases before leaf discoloration appears, a phenomenon botanists are just beginning to quantify. This intersection of traditional wisdom and cutting-edge biometeorology could revolutionize how we monitor forest health.

Policy implications are profound. Current carbon offset programs reward forest preservation based solely on carbon sequestration capacity. Dr. Eleanor Whitmore of the Potsdam Institute argues that "a forest drowning in its own methane emissions while storing carbon is like a diabetic saving sugar while bleeding insulin." Her team's modeling suggests that failing to account for methane could overestimate some forests' climate benefits by 18-23% by 2050.

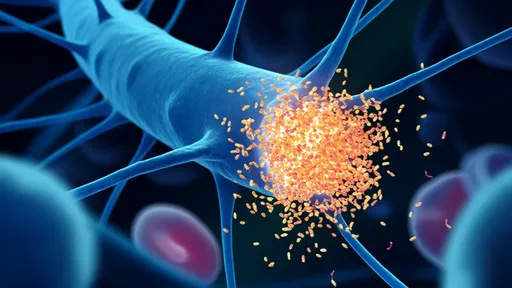

The microbial ecology within drought-stressed trees reads like a Shakespearean tragedy. As water becomes scarce, normally benign endophytic fungi inside tree xylem morph into opportunistic pathogens. Their metabolic shift produces hydrogen as a byproduct—a feast for methanogens. Researchers at Stanford's Department of Earth System Science found that inoculating trees with methane-oxidizing bacteria reduced emissions by 40% in lab conditions, though field applications remain experimental.

Financial markets are taking note. The London-based Environmental Derivatives Exchange recently launched the first "Forest Methane Futures" contracts, allowing investors to hedge against the climate risks posed by tree emissions. Meanwhile, the World Resources Institute has incorporated methane metrics into its Global Forest Watch platform, layering emission data over traditional deforestation alerts.

Perhaps the most haunting dimension is the historical context. Ice core analyses from Antarctica reveal anomalous methane spikes during ancient megadroughts that toppled civilizations. Today's instruments are detecting similar patterns as California's giant sequoias and Indonesian dipterocarps begin venting methane at unprecedented rates. The trees, it seems, have been trying to tell us something for millennia—we're only now learning to listen.

As research accelerates, fundamental questions remain. Why do some tree species emit methane while neighboring individuals don't? Can forests eventually adapt to drought by suppressing methanogens? And crucially—will this phenomenon reach a tipping point where it fundamentally alters global methane budgets? The answers may determine whether our forests remain climate allies or become unwitting adversaries in the coming decades.

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025