In a groundbreaking discovery that could revolutionize agricultural pest control, researchers have uncovered tobacco plants' remarkable ability to modulate ultrasonic frequencies as a defense mechanism against herbivorous insects. This natural "sonic weaponry" system represents one of the most sophisticated plant-animal interactions ever documented, blurring the line between botanical passivity and active biological warfare.

The study, published in Nature Phytobiology, reveals how Nicotiana attenuata (wild tobacco) plants emit high-frequency sounds when detecting specific caterpillar chewing vibrations. These ultrasonic emissions, ranging between 35-55 kHz, create an acoustic environment that disrupts insect nervous systems while attracting predatory arthropods that feed on the pests. What makes this defense extraordinary is the plant's capacity to fine-tune frequencies based on the attacker's species and developmental stage.

Field experiments demonstrated that tobacco plants exposed to recorded Manduca sexta (tobacco hornworm) feeding vibrations began emitting tailored ultrasonic pulses within 18 minutes. The plants showed frequency modulation patterns corresponding to the caterpillars' size - larger larvae triggered lower frequencies (35-42 kHz) while smaller instars induced higher pitches (48-55 kHz). This adaptive response suggests an evolutionary arms race where plants developed "acoustic profiling" capabilities against their primary herbivores.

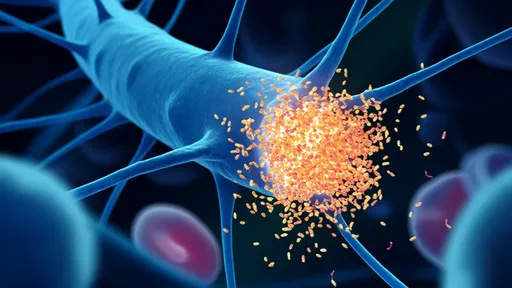

Electrophysiological recordings from pest insects revealed that these ultrasonic emissions cause neural interference, reducing feeding efficiency by 62-78%. The sounds appear to disrupt proprioception - the insects' sense of body position - causing uncoordinated movements and frequent falls from leaves. Simultaneously, the vibrations serve as dinner bells for predatory insects like Geocoris pallens (big-eyed bugs), which arrived at sounding plants 3.2 times faster than controls in behavioral assays.

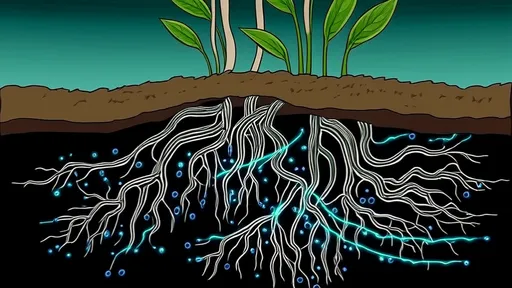

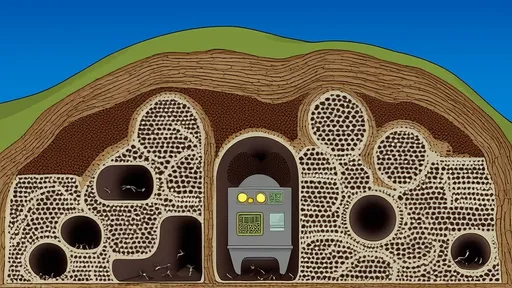

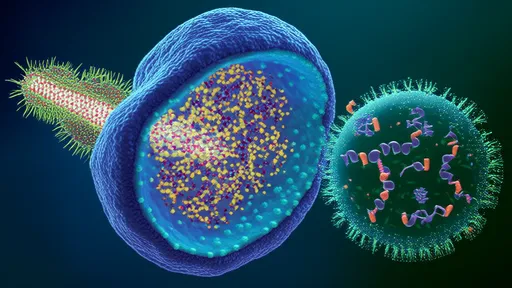

Mechanistically, the ultrasonic emissions originate from rapid cavitation events in xylem vessels when plants rapidly alter water pressure. This process, termed "hydraulic sonication," differs fundamentally from animal vocalization. The tobacco plant's stems act like biological violin strings, with tension-regulated xylem conduits serving as frequency-modulated sound sources. Genetic knockout experiments identified three key proteins involved in this process: AquaSon-1 (a modified aquaporin), VibroSpec-7 (vibration-sensing mechanoprotein), and FreqTune-3 (calcium-dependent frequency modulator).

Agricultural applications are already underway, with researchers developing "bio-sonic fences" that mimic the plants' ultrasonic signatures. Early trials show 40% reduction in pesticide use when combining these emitters with pheromone traps. The technology could prove particularly valuable for organic farming and integrated pest management systems. However, ecologists caution about potential unintended consequences, as many beneficial insects also perceive ultrasonic frequencies.

This discovery challenges traditional views of plant defense mechanisms, showing that chemical warfare (like nicotine production) represents just one facet of botanical protection strategies. The ultrasonic dimension adds complexity to our understanding of plant signaling and interspecies communication. Researchers speculate that similar systems may exist in other Solanaceae family members, potentially representing a widespread but overlooked defense paradigm.

Future research directions include investigating whether plants can "learn" new frequency patterns through epigenetic mechanisms, and if ultrasonic communication occurs between neighboring plants. The team also plans to study how climate change might affect these acoustic defenses, as drought stress alters xylem hydraulics - potentially modifying the plants' sonic weaponry effectiveness.

From an evolutionary perspective, this ultrasonic adaptation likely developed alongside the co-evolution of tobacco plants and their specialist herbivores. Fossil evidence suggests early Nicotiana species already possessed modified xylem structures 8-10 million years ago, coinciding with Manduca moths' radiation. The current study provides the first functional evidence linking these anatomical changes to biological sonication capabilities.

As research continues, the agricultural sector watches closely. Patent applications for ultrasonic crop protection systems have surged 300% since these findings were announced. Meanwhile, bioacoustics researchers are re-evaluating decades of plant sound recordings, wondering how many other botanical sonic weapons might have been previously dismissed as physiological artifacts.

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025