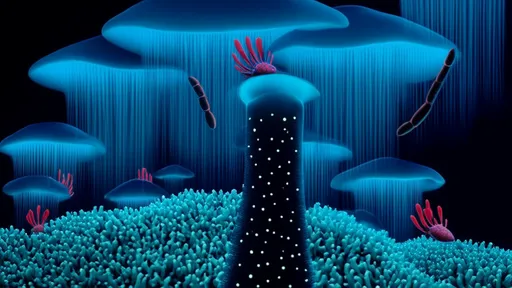

Beneath the shimmering surface of tropical oceans lies one of nature’s most intricate and vital conversations—a chemical dialogue between coral and the microscopic algae known as zooxanthellae. This exchange, fundamental to the survival of coral reefs, represents a sophisticated language of symbiosis that scientists are only beginning to decode. The partnership, forged over millennia, enables reefs to thrive in nutrient-poor waters, building ecosystems that support nearly a quarter of all marine species.

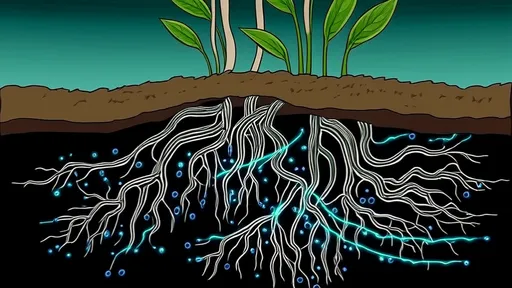

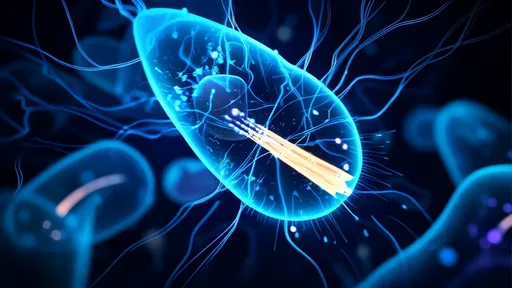

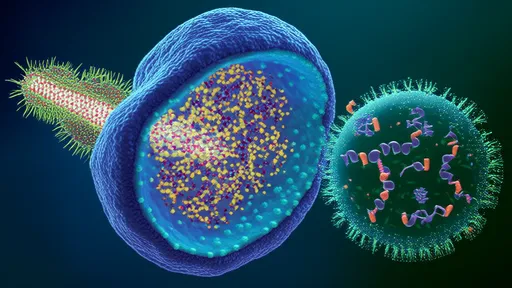

At the heart of this relationship are the zooxanthellae, photosynthetic dinoflagellates that reside within the coral’s tissues. These algae harness sunlight to produce sugars and other organic compounds, a portion of which they transfer to the coral host. In return, the coral provides the algae with a protected environment and essential nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus. This mutualistic exchange is the engine behind the coral’s ability to construct massive calcium carbonate skeletons, forming the complex structures we recognize as reefs.

The chemical dialogue begins with the exchange of nutrients. Zooxanthellae convert carbon dioxide and water into glycerol, glucose, and amino acids through photosynthesis. These compounds are then released into the coral’s tissues, where they serve as a primary energy source. The coral, in turn, recycles waste products like ammonia, which the algae utilize to synthesize proteins and other vital molecules. This efficient recycling mechanism allows both organisms to flourish in environments where nutrients are scarce.

But the conversation extends beyond mere nutrient trade. Researchers have discovered that chemical signals regulate the density and behavior of zooxanthellae within the coral host. For instance, the coral can modulate the algal population by controlling the availability of nitrogen, ensuring that the symbiosis remains balanced. Too many algae could lead to oxidative stress under high light conditions, while too few would deprive the coral of essential energy. This delicate equilibrium is maintained through a continuous exchange of chemical cues.

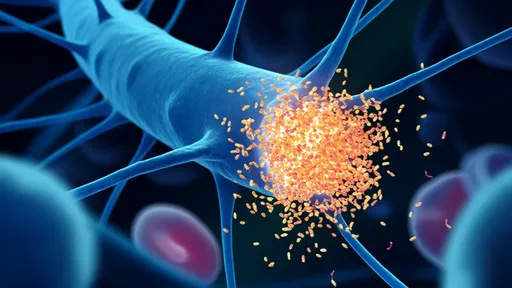

One of the most critical aspects of this dialogue is its role in mitigating environmental stress. When corals experience elevated temperatures or increased light intensity, the symbiotic relationship can break down, leading to coral bleaching—a phenomenon where corals expel their zooxanthellae, turning white and potentially dying. However, under normal conditions, chemical signals help both partners acclimate to minor fluctuations. For example, corals produce antioxidants and heat-shock proteins that protect the algal symbionts from damage, while the algae contribute compounds that enhance the coral’s resilience.

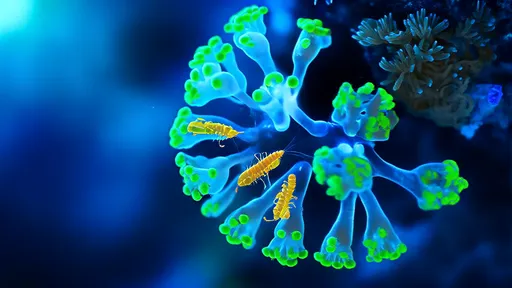

Recent advances in molecular biology have allowed scientists to delve deeper into the molecular language of this symbiosis. Studies using transcriptomics and metabolomics have revealed that both corals and zooxanthellae alter their gene expression and metabolic profiles in response to each other’s presence. For instance, corals upregulate genes involved in nutrient transport and stress response when harboring zooxanthellae, while the algae adjust their photosynthetic machinery to optimize energy production without harming the host.

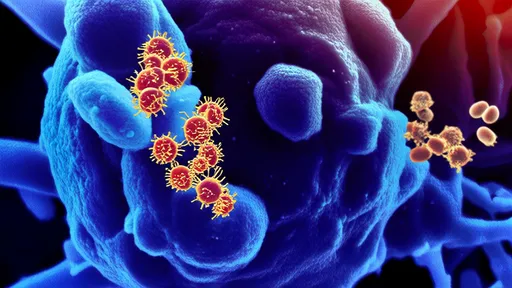

Moreover, the initial establishment of the symbiosis involves a complex courtship of chemical signals. Coral larvae must recognize and uptake specific strains of zooxanthellae from the surrounding water—a process mediated by signaling molecules such as lectins and glycoproteins. These molecules act like a handshake, ensuring compatibility between the host and symbiont. Mismatches can lead to inefficient partnerships or even rejection, highlighting the specificity of this ancient alliance.

Climate change and human activities now threaten to disrupt this finely tuned dialogue. Rising sea temperatures, ocean acidification, and pollution can interfere with the chemical signals that sustain the symbiosis. For example, elevated temperatures can cause zooxanthellae to produce reactive oxygen species that damage coral tissues, triggering bleaching. Similarly, acidification can impair the coral’s ability to synthesize the skeletal structures that provide a home for the algae.

Understanding the chemical password of this dialogue is not merely an academic pursuit—it holds the key to conserving and restoring coral reefs. By deciphering the signals that promote resilience, scientists hope to develop interventions that could help corals withstand environmental stressors. Some researchers are exploring the use of probiotics to enhance the coral’s microbiome, while others are investigating selective breeding of heat-tolerant zooxanthellae strains.

The story of coral and zooxanthellae is a testament to the power of collaboration in nature. Their chemical conversation, honed over millions of years, underscores the interdependence that defines life on Earth. As we face unprecedented environmental challenges, listening to and learning from this dialogue may inspire solutions that protect not only coral reefs but the countless species—including humans—that depend on them.

In the end, the silent language spoken between coral and zooxanthellae reminds us that even the smallest conversations can have profound consequences. It is a language of survival, written in the chemistry of the ocean, and its preservation is essential for the future of our planet’s most vibrant underwater landscapes.

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025