In the perpetual darkness of the deep sea, where sunlight cannot penetrate, scientists have uncovered an extraordinary biological phenomenon: geothermal-powered photosynthesis. A recent study reveals that certain bacteria thriving near hydrothermal vents utilize infrared radiation from these vents to drive the Calvin cycle, a process previously thought to be exclusively dependent on sunlight. This discovery not only redefines our understanding of photosynthesis but also opens new avenues for exploring life in extreme environments.

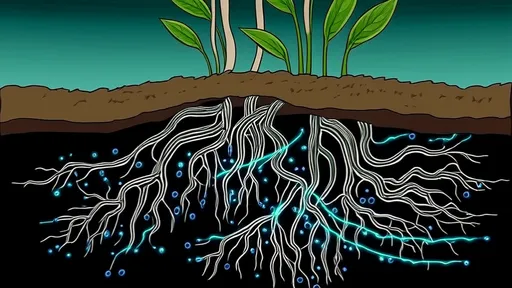

The hydrothermal vents, often referred to as "black smokers," spew superheated water rich in minerals and gases. These vents emit a faint glow of infrared light, a byproduct of their intense thermal activity. Researchers have now identified a group of thermophilic bacteria that harness this infrared light to fix carbon dioxide, much like plants do on the surface. The implications of this finding are profound, suggesting that photosynthesis could occur in the absence of sunlight, powered solely by geothermal energy.

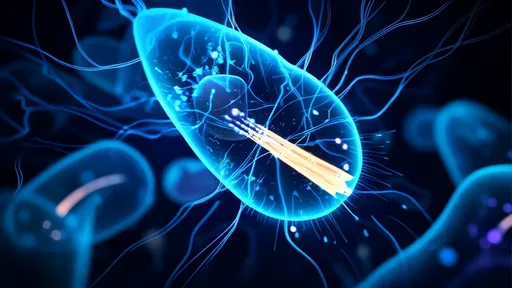

These bacteria, dubbed "geothermal phototrophs," possess specialized pigments capable of absorbing infrared wavelengths. Unlike chlorophyll, which absorbs visible light, these pigments are optimized for the low-energy photons emitted by hydrothermal vents. The bacteria then channel this energy into the Calvin cycle, converting carbon dioxide into organic molecules. This adaptation allows them to thrive in an environment where traditional photosynthesis would be impossible.

The discovery challenges long-held assumptions about the energy sources that can sustain life. On Earth, sunlight has been considered the primary driver of photosynthesis, but geothermal phototrophs demonstrate that alternative energy pathways exist. This raises intriguing questions about the potential for similar life forms on other planets or moons with geothermal activity but no sunlight, such as Jupiter's Europa or Saturn's Enceladus.

One of the most striking aspects of this finding is the efficiency of these bacteria in utilizing infrared light. Infrared photons carry less energy than visible light photons, yet geothermal phototrophs have evolved mechanisms to compensate for this difference. Their photosynthetic apparatus appears to be highly specialized, maximizing energy capture from the faint glow of hydrothermal vents. This efficiency underscores the remarkable adaptability of life in extreme conditions.

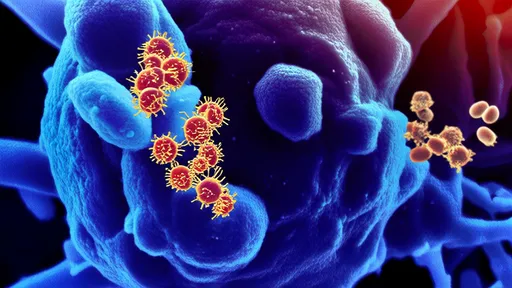

Scientists are now investigating the genetic and biochemical mechanisms that enable this unique form of photosynthesis. Preliminary analyses suggest that geothermal phototrophs share some genetic similarities with surface-dwelling photosynthetic bacteria, but they also possess distinct genes that may be responsible for their infrared absorption capabilities. Understanding these genetic differences could provide insights into the evolution of photosynthesis and the potential for engineering similar systems in the lab.

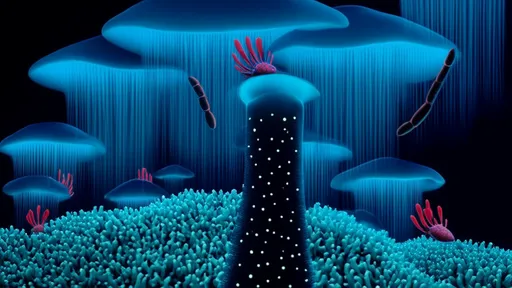

The ecological role of these bacteria in deep-sea ecosystems is another area of active research. Hydrothermal vents are oases of life in the deep ocean, hosting diverse communities of organisms that rely on chemosynthesis. The presence of geothermal phototrophs adds a new layer of complexity to these ecosystems, as they represent a previously unknown energy source. Their ability to fix carbon dioxide could influence the overall productivity of vent communities and the cycling of nutrients in the deep sea.

This discovery also has implications for astrobiology. If photosynthesis can occur without sunlight, the range of environments where life could potentially exist expands dramatically. Geothermal activity is common on many planetary bodies, and the presence of infrared-driven photosynthesis could make these worlds more habitable than previously thought. Future missions to icy moons with subsurface oceans may now include searches for similar microbial life forms.

Beyond its scientific significance, the study of geothermal phototrophs could inspire new technologies. The ability to harness low-energy infrared light for carbon fixation has potential applications in bioenergy and carbon capture. Researchers are exploring whether these bacteria or their pigments could be used to develop more efficient solar cells or systems for removing carbon dioxide from industrial emissions.

The deep sea continues to surprise us with its resilience and ingenuity. The discovery of geothermal-powered photosynthesis is a testament to the adaptability of life and the untapped potential of Earth's most extreme environments. As scientists delve deeper into the mysteries of hydrothermal vents, who knows what other revolutionary findings await in the abyss?

This research underscores the importance of exploring Earth's least understood ecosystems. Every expedition into the deep sea brings new revelations, challenging our assumptions and expanding the boundaries of what we consider possible. The geothermal phototrophs are just one example of how life finds a way, even in the most inhospitable corners of our planet.

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025