In the intricate world of biomechanics, few natural phenomena rival the astonishing jumping ability of fleas. These tiny insects, often measuring just a few millimeters in length, can launch themselves distances up to 200 times their body length. For decades, scientists have marveled at this capability, but recent breakthroughs have revealed the true marvel behind their power: an ultra-resilient protein structure in their legs that behaves like a biological titanium alloy.

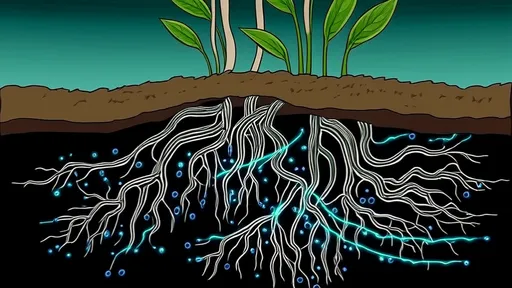

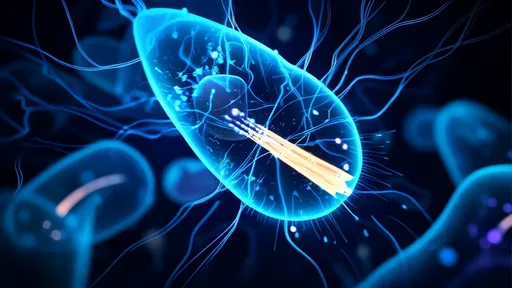

The secret lies in a specialized protein called resilin, a rubber-like material that stores and releases energy with near-perfect efficiency. Found in the flea's hind legs, this protein acts as a natural spring, compressing and decompressing with incredible speed. What makes resilin extraordinary is its ability to withstand repeated stress without losing elasticity—a property that has long eluded human-engineered materials.

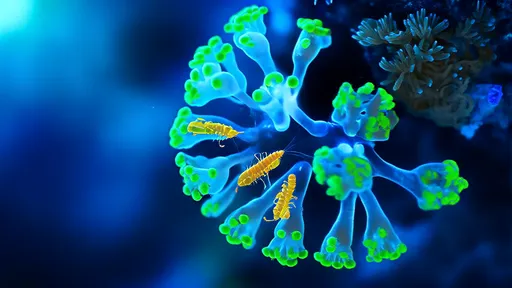

Researchers at the University of Cambridge recently published a study in Nature Biomimetics detailing how the molecular structure of resilin mimics the durability of synthetic alloys. Using advanced electron microscopy, they observed that the protein forms a networked matrix of coiled chains, similar to the crystalline lattice in titanium. When compressed, these chains absorb energy like a coiled spring, then snap back to their original shape with minimal energy loss. This "superelastic" behavior allows fleas to jump thousands of times without wear.

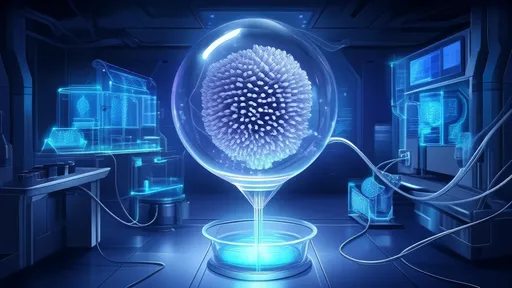

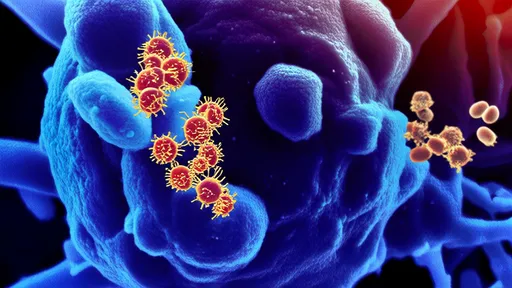

Engineers are now racing to replicate this biological marvel. A team at MIT has developed a synthetic version of resilin by modifying elastin polymers, creating a material they call "bio-titanium." Early tests show it can endure over a million stress cycles without degradation, outperforming conventional rubber and even some metal alloys. Potential applications range from medical implants to shock-absorbing exoskeletons for athletes.

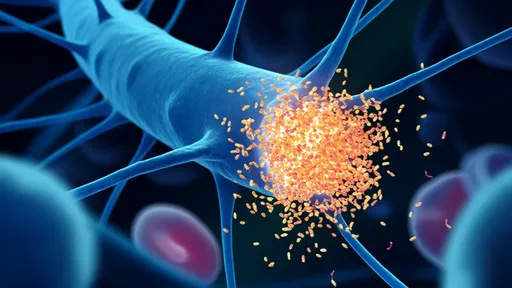

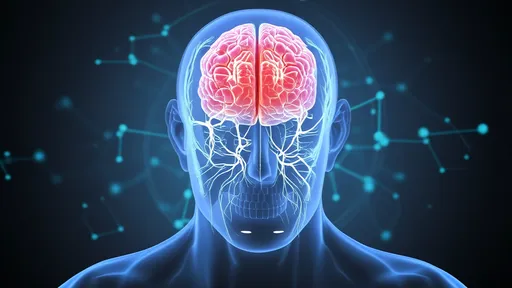

But nature's design still holds mysteries. Unlike human-made springs, which fatigue over time, resilin actually self-repairs at the molecular level. Dr. Elena Petrov, a biophysicist leading the Cambridge study, notes that the protein contains embedded amino acids that realign damaged bonds. "It's as if the material has billions of microscopic repair crews working around the clock," she explains. This self-healing property, absent in even the most advanced alloys, could revolutionize material science if harnessed.

The implications extend beyond engineering. Evolutionary biologists now believe resilin played a crucial role in insects adapting to diverse environments. Fossils show that ancient fleas from the Jurassic period had similar leg structures, suggesting this "biological titanium" has been perfecting itself for over 150 million years. As researcher Dr. Marcus Wei remarks, "We're not just looking at a material—we're seeing evolution's masterpiece of mechanical design."

While synthetic resilin is still in development, its potential is undeniable. From robotics to aerospace, materials that combine elasticity with endurance could redefine durability. The flea, once merely a pest, now inspires a new frontier where biology and technology converge—one jump at a time.

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025