In the intricate dance of molecular biology, few phenomena have captured researchers' attention quite like the phase transition of TDP-43 proteins and their surprising role in memory consolidation. Recent breakthroughs suggest these proteins may function as molecular glue, solidifying the neural connections that form our most cherished memories. The implications of this discovery ripple across neuroscience, offering fresh perspectives on both cognitive function and neurodegenerative diseases.

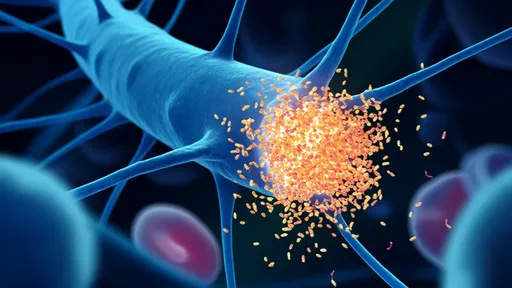

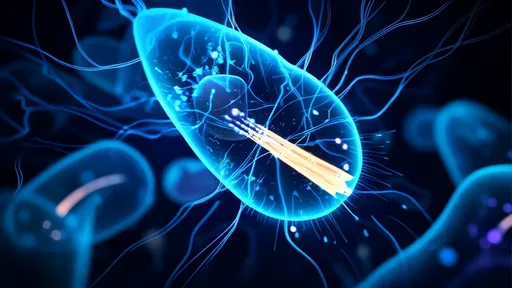

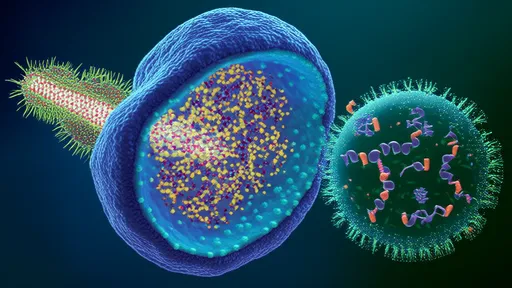

The TAR DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP-43) has long been known to scientists, but its starring role in memory formation represents a paradigm shift. When neurons fire during learning experiences, TDP-43 proteins undergo liquid-liquid phase separation, transforming from soluble molecules into gel-like droplets within synaptic compartments. This physical change appears to stabilize the molecular machinery required for long-term memory storage, essentially "gluing" together the components needed to preserve our experiences.

What makes this discovery particularly remarkable is how it bridges the gap between molecular biology and cognitive science. The phase transition behavior of TDP-43 provides a physical substrate for memory consolidation that previous biochemical models couldn't fully explain. As these proteins solidify into hydrogel-like states, they create stable microenvironments where memory-related proteins can interact with exceptional efficiency, protected from the constant molecular turnover that characterizes living cells.

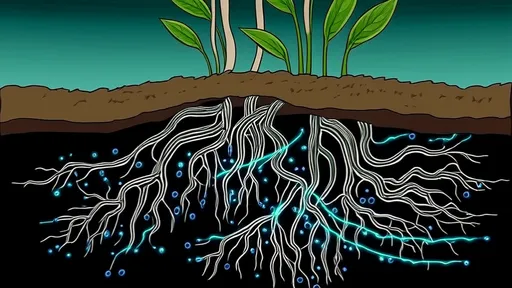

Neuroscientists have observed that TDP-43 droplets preferentially form at activated synapses following learning experiences. The proteins appear to respond to neural activity patterns, aggregating precisely where memories are being encoded. This targeted solidification creates what some researchers describe as "molecular memory tags" - physical markers of important synaptic events that need preservation. The process resembles how certain adhesives cure only when exposed to specific conditions, providing both stability and specificity.

The implications for memory disorders could be profound. In healthy brains, TDP-43 phase transitions are reversible and carefully regulated. However, in conditions like Alzheimer's disease and frontotemporal dementia, these proteins often form irreversible, pathological aggregates. The new understanding of TDP-43's normal function in memory suggests that these diseases might represent, at least in part, a corruption of the very mechanism that usually preserves our recollections.

Laboratory experiments demonstrate that disrupting TDP-43 phase separation impairs memory formation in animal models, while enhancing the process appears to boost certain types of learning. These findings have sparked interest in developing compounds that could modulate TDP-43's phase transition properties. Such interventions might one day help treat memory disorders, though researchers caution that much work remains to translate these discoveries into therapies.

Beyond medical applications, the TDP-43 story reshapes our fundamental understanding of how biological systems store information. The protein's dual nature - functioning normally as part of a dynamic memory system but causing harm when dysregulated - illustrates the delicate balance required for cognitive function. It also highlights how evolution repurposes basic physical phenomena, like phase separation, for complex biological functions.

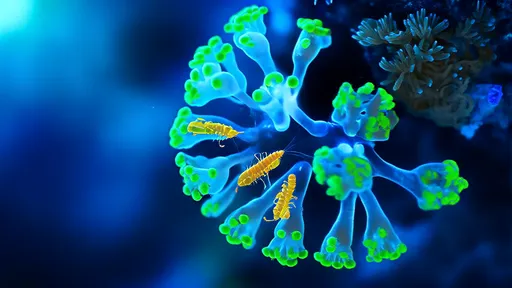

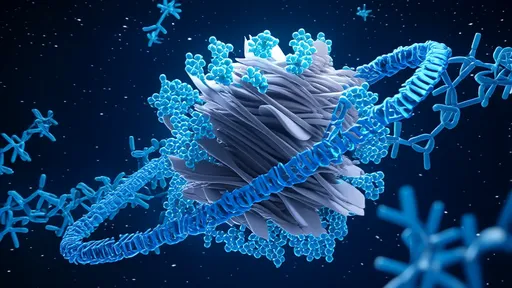

As research continues, scientists are mapping the intricate choreography between TDP-43 and other memory-related molecules. Early evidence suggests these proteins don't work in isolation but form complex condensates with RNA and other partners. These molecular assemblies appear tailored for specific types of memories, potentially explaining why different experiences have varying degrees of persistence in our minds.

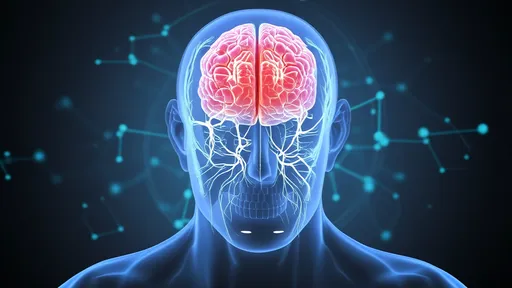

The discovery of TDP-43's role in memory also raises fascinating questions about the physical nature of cognition. If memories rely, even partially, on protein phase transitions, does this mean our recollections exist in a state between liquid and solid? How does this physical state influence memory retrieval and modification? These questions blur traditional boundaries between chemistry, physics, and neuroscience.

Looking ahead, researchers anticipate that understanding TDP-43's molecular glue properties will open new avenues for investigating memory enhancement and preservation. The protein's behavior provides a tangible target for interventions aimed at maintaining cognitive function during aging or after injury. Moreover, it offers a new lens through which to view the mysterious process that transforms fleeting experiences into lasting memories.

While much remains to be discovered about TDP-43 and memory, one thing is clear: the boundary between molecular biology and psychology grows increasingly porous. The realization that something as fundamental as protein phase transitions underlies our most personal experiences challenges us to rethink what memory really is - not just as a psychological phenomenon, but as a physical process written in the language of molecules.

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025